As it turns out, yesterday was the ninth anniversary of the death of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. As such, there was a celebration of his life and legacy at New Afrika Shrine - the reconstituted version of the club Fela maintained as his personal court, soapbox, and alternate reality for more than two decades - as a prelude to the massive "Felabration" slated for October.

Denis and I want to go to the Shrine. We're both huge Fela fans; in fact, Fela was a bit of a catalyst in our friendship. We "met" a few years ago on the Okayplayer music board when he posted a poll posing the question "Who is the most prominent African musician - Myriam Makeba, Franco, Manu Dibango or Meiway?" Outraged, I immediately fired back with "How the hell you gonna make a post about important African musicians and not include Fela?" He calmly explained to me that he didn't really know all that much about Fela, having grown up in Francophone Africa, where the influence of a figure like Franco loomed a little larger. The truth is, at the time I was just really getting about Fela's music myself.

By the time I was coming up in the 1980s, Fela was a shadow of the fiercely creative and popular musician he had been in the previous decade. Since the 1977 government-mandated firebombing of his home and the resultant death of his mother, he seemed to be become less known for his music than for his controversial public antics--the weed, the nudity, the polygamy, the blasphemy, the highly theatrical presidential campaigns, the frequent trips to jail and drawn-out court cases--kinda like 2Pac would be in the '90s. His music wasn't played much on the radio and when it was, it tended to be humourous, relatively innocuous dance records like "Open and Close" and "Excuse-O." Our government was a fairly repressive military dictatorship, and just whistling one of Fela's more anti-establishment tunes like "Zombie" within earshot of any soldier, policeman, customs officer or even a traffic warden was enough to get you beaten within an inch of the pearly gates and thrown in jail.

In the eyes of a lot of middle-class parents (like mine), messing with Fela was a gateway to a seriously fucked-up life and they endeavoured to insulate their children from his influence the same way you do your best to keep your kids away from crack pipes, stripper poles and religious cults. Because, really, that's kinda what Fela fandom was: a cult. But it wasn't just a cult full of thieves, thugs and hookers, like most people thought; its membership spanned across all walks of society, including some sectors of the government. I was a late convert: Fela didn't really capture my soul until the day I was getting on the plane to leave Nigeria in the early '90s, but now that I was back, I was looking forward to making a pilgrimage to his sacred temple. Me and Denis had planned a trip to the Shrine for a long time and this seemed the best time to make it happen.

Except that Koko wasn't trynna hear it.

Not that he's not a Fela fan; he is--hardcore. In fact, he was the one who first introduced me to "Baba 70"'s music (or tried to, anyway) back in high school, and he always has a Fela tape in the car (along with a cassette of really cheesy '80s funk & R&B and Toni Braxton's first album, which he plays specifically when he wants to torture me and Denis). As a true Fela-head, he's been to the Shrine a couple of times and he had the portent that the night's event was going to be like an area boy* homecoming festival; unless one absolutely, positively needs to experience the feeling of blood gushing from one's forehead like a geyser as multiple beer bottles shatter upon one's cranium, it might be a good idea to put a considerable distance between oneself and that general area. Me and Denis tried to persist, but Koko was the one driving and if he said we weren't going to the Shrine, then we weren't going to the Shrine.

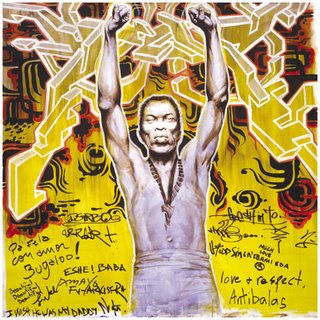

So there we were yesterday evening, sitting in the middle of one of Lagos's trademark traffic jams, listening to the radio. All the stations are playing Fela's classic jams (well, the two that weren't playing Christina Aguilera's "Ain't No Other Man" and that dreadful new Beyonce song every twelve minutes, anyway). As "Roforofo Fight" comes on, I'm reminded exactly how much Fela's music informed the creation of TOO MUCH BEAUTIFUL WOMAN. The very first scene I wrote in the script (the one where Boy scuffles in the street with the market woman Madam Kuku as a jeering crowd gathers around) was directly inspired by the abrupt, chaotic energy of this song. The second scene I wrote (which is now the first scene in the script) was inspired by "Water No Get Enemy." The go-slow scene was dictated by, of course, "Go Slow." Hell, even the fast-paced, semi-cartoonish mise-en-scene was less an attempt to emulate Guy Ritchie than it was a desire to achieve the kind of collage of vivid detail, grotesque humour and jarring juxtapositions that characterized the sleeve art Ghariokwu Lemi created for Fela's albums.

These thoughts only reinforced my belief that a visit to Fela's house would restore my sagging confidence, so I tried to gain some leverage for my case by cloaking my selfish desires in the guise of selfless professionalism:

"You know... This might be a good way to earn some much-needed production scratch. Straight No Chaser would probably pay good money for some pictures of that event."

"If you even THINK of taking a camera into that place---!!" Koko snapped. He took a breath, regained compsure and then sighed wearily. "See... That's the reason why we're not going to the Shrine. Because I don't plan to be the one to explain to your parents the events surrounding the death death of their son. Besides, weren't you the one who just had to see Yinka Davies tonight?"

Ah yes. Let's get things straight about that. While I do have the tendency to sometimes come off as an obsessive crackpot who's seen Vertigo four or five times too many, there was a fairly logical and practical reason for my yen to meet with Yinka. In fact, there were at least two such reasons:

1. At five o'clock in the morning, after two and a half hours of watching Nigerian videos that mostly looked like this

Get this video and more at MySpace.com

or this

the simplicity and spirituality of Yinka's video washed over me like a moment of clarity.

[I really wish I could include a clip of the video so you could see what I'm talking about, but I just can't find it anywhere.]

2. The Koyaanisqatsi-esque montage of the video impressed upon me the fact that what I really needed to hold this film together was a powerful score like the one Philip Glass provided.

Last time we were in Lagos, a ladyfriend mentioned to me that Yinka Davies was an old acquaintance and that I should give her a call to provide some music for the movie. I wasn't that interested, though. Pretty much from the beginning, we knew what kind of music we wanted for the movie. We were aiming squarely for a retro-romantic feel, so we wanted some afrobeat by Fela (or if that turned out to be too expensive, one of the many Fela disciples) and vintage highlife, rumba and cha-cha-cha from the 1950s and '60s. The idea of using contemporary music wasn't something we had on the agenda at all. In fact, we had something of a maxim: "No jeans and no rapping!" [I'll explain the jeans thing later, fam] But all of a sudden, I felt that Yinka probably did have a certain sensibility that could add something to the vision we were trying to realize.

So I called Yinka. I found her to be warm and cordial on the phone, though she seemed a bit curious about how I had gotten her number. I told her that B____ had given it to me. I told her that I had been a fan of her work as a lead vocalist in Lagbaja's band.

"That was a long time ago," she laughed.

"I heard you were doing some stuff with the Jazzhole folks now, right?"

"Well, I've worked with them in the past... But not at the moment."

"So... uh, what else have you been up to? I heard you were on the new Tony Allen record, too."

"Oh yes! Have you heard it?"

"No... Not yet. Heard good things about it, though." [I've since heard it; here's one of the tracks Yinka features on, "Losun"]

"So what's the deal, then? What can I help you with?"

I told her that I was a filmmaker and I was looking for music for my movie. I told her about seeing her video at 5 a.m. and I hoped that I didn't sound like a crazy person.

She was quiet for a moment and then she said "Why don't you come over and see me today?"

I was quite pleased.. If she's actually inviting me over to her home, that means that I didn't sound crazy, right?

Or maybe it just meant that I did sound crazy, but that she recognized a kindred spirit.

(to be concluded)

___________________________________________________

* The “area boy” is the Naija equivalent of the “rudeboy” or “gangsta” or “generally thugged-out individual that you don’t want to mess with”

4 comments:

This blog is saudades for me. I remember being in grad school and trying to imagine how Lagos and Calabar were while you guys were filming and occasionally being able to read you or Bongo's blog to make my wanderings more colorful.

glad to hear that, dadakiss!

Well....where's the conclusion man??...lol

LOL it's coming, man... it's coming!

Post a Comment